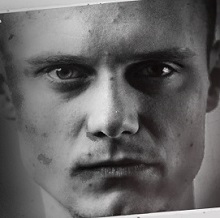

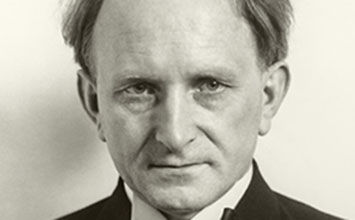

In the book, this black-and-white photograph is given a full page. I’m looking at one such image in Dawoud Bey’s magnificent career retrospective, “Seeing Deeply” (2018). Sometimes this response is amplified when it’s a portrait of someone not famous, a face that isn’t burdened with predetermined knowledge.

This is not to deny any of the wonder or gratitude you feel before a superb portrait. But physiognomy, the idea that faces carry meanings, still haunts the interpretation of portraiture. Phrenology has rightly been consigned to the dustbin of history. After all, we no longer believe you can determine someone’s personality by measuring their skull with a pair of calipers. We easily link the people’s facial features to the content of their character. We talk about strength and uncertainty we praise people for their strong jaws and pity them their weak chins. We tend to interpret portraits as though we were reading something inherent in the person portrayed. The catalog text at the Library of Congress adds that he is “peering uncertainly into the camera.” But is that true? How would we verify it? His dark coat has a high collar, and his hair is tousled. Cornelius held his pose for several minutes in the bright October sun in 1839. One of the first photographic portraits, if not the first, was a self-portrait daguerreotype made by a 30-year-old amateur chemist from Philadelphia named Robert Cornelius. But the two eventually came together, and now their pairing seems so natural that it’s as though photography was invented for making portraits. And for more than a dozen years after photography’s invention, it was practically impossible to make a photographic portrait: the required exposure times were too long. Portraiture existed long before photography was invented.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)